|

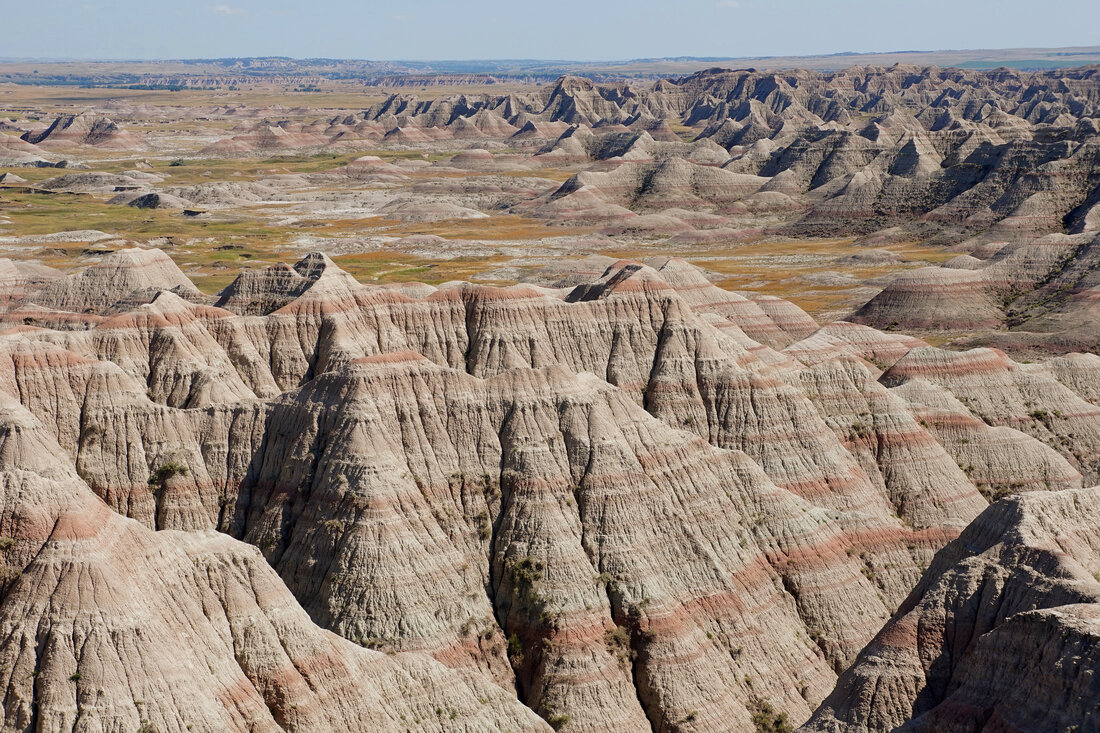

Before I was six years old, my grandparents and my mother had thought me that if all the green things that grow were taken from the earth, there could be no life. If all the four-legged creatures were taken from the earth, there could be no life. If all the winged creatures were taken from the earth, there could be no life. If all our relatives who crawl and swim and live within the earth were taken away, there could be no life. But if all the human beings were taken away, life on earth would flourish. That is how insignificant we are. ~ Russell Means, Oglala Lakota Nation (1939-1912) And yet we are so obsessed with ourselves. We bring absolutely everything to our own: very narrow viewpoint. To us, everything is telling our story. Everything is about us: weather, changes of season, joys and miseries of our lives. Even the pandemic. We are the very center of our own universe and all the planets turn around us, celebrating our sorrows and happy moments, likes, dislikes, our desires and our needs. We’re living in a self-centered world, and even when we say that we want to belong, it is about us. Not about the belonging. We do not even see it as strange. The goodness of the Badlands is that they take you away from this obsession with yourself to some alien, timeless, selfless space, where nothing is about you. The Badlands are also the perfect vehicle for time travelers: one can almost see the planet the way it looked like before our ancestors were born. But you would never call the Badlands “home”. This is where the Earth says “I really don’t need you, humans. I did without you for over 4 billion years. You’ve been with me for a few seconds of my time. This land is not yours, it's mine." And yet, visiting the Badlands feels like landing on another planet, and it was for good reason that someone proposed naming this nature park "Wonderland National Park". It also makes perfect sense that the Badlands are called one of the most wonderful and underrated American national parks. I've been around the world a lot, and pretty much over our own country, but I was totally unprepared for the revelation called the Dakota Badlands – wrote Frank Lloyd Wright. - What I saw gave me an indescribable sense of mysterious elsewhere - a distant architecture... an endless supernatural world more spiritual than Earth but created out of it. 75 million years ago the Badlands were a shallow sea, and after eons a land under it rose, pushing the water away. After another few millions years, the subtropical forest changed into savanna, and today the Badlands are an area of colorful cliffs and hills, and a home to the largest mixed-grass prairie in the park system. The hills change with the weather, light, and time of day. Every moment, every curve on the road, a completely new landscape unfolds before us, and a play of light creates new patterns. Each view is new, although millions of years old. Every year wind and rain erodes the soft rocks (at a rate of about one inch per year), and the erosion slightly changes the shape of the formations, creating new pinnacles, spires, caves, and jagged edging, which makes Badlands an even more fascinating place. The Badlands is an open-hike park, so you are free to explore the features of numerous trails and overlooks, but you can also park in the middle of nowhere and go off the beaten path to wander (cautiously) among the rocks like the first European travelers, looking for a passage. Maybe stop by one of the impressive geologic vistas, a bizarre “ancient castle” or a “city in ruins”? Maybe rest under the lustrous leaves of a cottonwood tree? What scenic marvels we will see if we come back here next year? Sioux called this land Mako Sica, or the bad lands, as the climate here is very harsh: from brutal cold, wind, and the snows of winter, to the extreme heat, dryness, and frequent fires in summer. The water is almost undrinkable. Steep slopes, deep canyons, and sudden precipices still make travel difficult. The French-Canadian trappers also called it “les mauvaises terres” (bad lands). Geologists visiting the land in the 19th century were often troubled, and some would lament that the “animate and inanimate nature in Badlands was against them”. Some travelers admired these landscapes as “solitary, grand, chaotic, as it came from the hands of Him” (Captain John Todd, as quoted in the book “Badlands National Park” by Jan Cerney), some were terrified: “No words of mine can describe these Bad Lands. They are somewhat as Dore pictured hell” (artist Frederic Remington). The Badlands prairie looks alive, but life here needs to persist. Seeds that fall among the rocks may not thrive. Ground water may be too deep for shallow roots. Grasslands are divided by rocky formations, like the famous Badlands Wall that separates the lower prairie in the south and upper prairie to the north. Without today's roads moving through the Badlands it must have been really difficult, or almost impossible. Traveling in the times of pandemic can be seen as irresponsible and unjustified (except for travels that are obviously purposeful, like visiting family or someone in need), it may also be a way of approaching healing from within. Even in our culture, where travel became a form of consumption, it still has a potential to be a medicine. Locked in our small worlds, small selves, small apartments, small or big houses, we yearn to experience more space, more relation, more belonging. And after going within: in shame of the realization that we have brought this disease upon ourselves through our irresponsible economy and false values (extensive traveling included), and after spending a considerable, painful, fruitful time indoors, we just want to go outside more. Ready to be touched (and perhaps transformed). This time going outside may not be a sign of running away from our inner life to conquer the world and gain more self-worth; to feel better, look better or appear better, or to lose ourselves in whatever travel offers. It may be a sign of a wish to live a more meaningful and relational life. Then the Badlands becomes more than a commodity. And if it is true that there is this deep symmetry between what’s inside and outside, our trip to the Badlands may be a journey to one of the most difficult and isolated parts of our own life. Our own inner hard passage, bad land… only to learn that even if it is a difficult place, the journey carries also beauty and potential of freeing us from our own barriers, expectations, images, and forms. Our alien and abandoned places are a medicine for the soul. When we face them, the light pours. Wandering through the Badlands during the pandemic, in a pioneering spirit, we take a 30-mile Badlands Loop that provides an opportunity for additional stops and explorations. The Badlands are never too crowded, especially during late spring (although I also read that they host about one million visitors annually), but this summer they are deserted. The austere, moon-like landscape and hot wind enter our senses like an intense dream. They empty our minds and deprive us of a sense of time and form. Their unfamiliarity creates in us more genuine response to whatever is this call. When we see our global crisis as an opportunity to stay in a bad place long enough to really see and experience it, then we can grieve our losses, look for a way to heal, and emerge from within this bad land stronger, quieter, more peaceful and more real, equipped with new medicine, new feelings, a new map, and the will that may help us to unite, to become a more useful part of a greater whole.  The Badlands are not bad. They are quite beautiful. Their organic growth and metamorphoses make you feel like you’re facing some unknown creative impulse that's going on in Nature. The soil, heat, aroma, hills, shapes and colors create a link to some unknown creative part inside ourselves. Frank Lloyd Wright touched upon that, when writing about the Badlands in 1935: Let sculptors come to the Badlands. Let painters come. But first of all the true architect should come. He who could interpret this vast gift of nature in terms of human habitation so that Americans on their own continent might glimpse a new and higher civilization certainly, and touch it and feel it as they lived in it and deserved to call it their own. Yes, I say the aspects of the Dakota Badlands have more spiritual quality to impart to the mind of America than anything else in it made by man's God. And maybe the Badlands are not that otherworldly either. Perhaps they are rather inner-worldly – as Japanese Dakota native poet Lee Ann Roripaugh speaks of them in her intricate poem “Badlands”: (…)some say moonscape, or otherworldy, as if to mean something alien, sandwiched between the banality of kitschy Sinclair station dinosaurs and Wall Drug’s ubiquitous billboards I think not moonscape but earthscape, not otherworldly, but innerworldy, not alien, but indigenous, as in always already from and of as in sovereign, as in not ours(…) There is only one mistake you are making: you take inner for the outer and the outer for the inner. ~ Nisargadatta Maharaj If we stay in Badlands long enough, we will feel that we do belong. Dizzying landscape, bison and pronghorn, the unexpected gaze of sunflowers from the tall grass, and unsettling curves on the road stop us but do not stop us from experiencing this great silence of a wilderness which is miles and miles long. This unwelcoming land actually supported humans for over 11 thousands years (being a home for mammoth hunters, nomadic tribes, and the Lakota Sioux).

This unusually beautiful land could even have been our home before we came to this world (if only we could see our original faces before our mothers and fathers were born...) and before we became these weird humans that we cannot live without and that we run away from. And maybe like in this strange prophecy, the Badlands will one day become a land for what we may become? Lidia Russell

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

TravelingI never underestimate Archives

July 2023

|